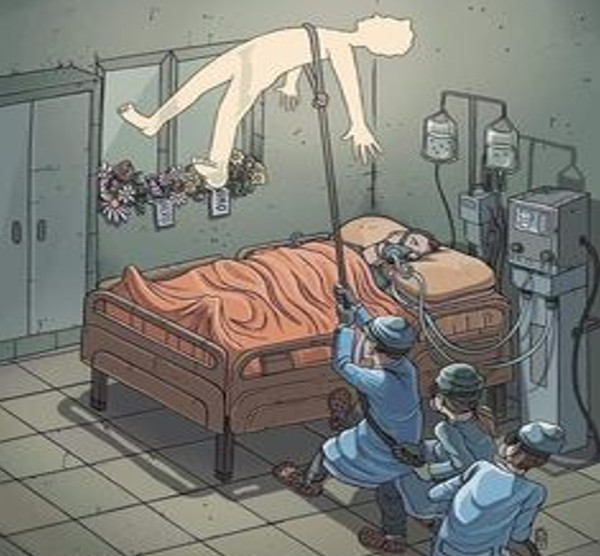

Сейчас происходит много

наводнений, дождей и снегопадов и, если вы оказались, окружённые

водой/снегом, нет электричества и нет интернета, и не знаете, что

делать дальше, то делайте

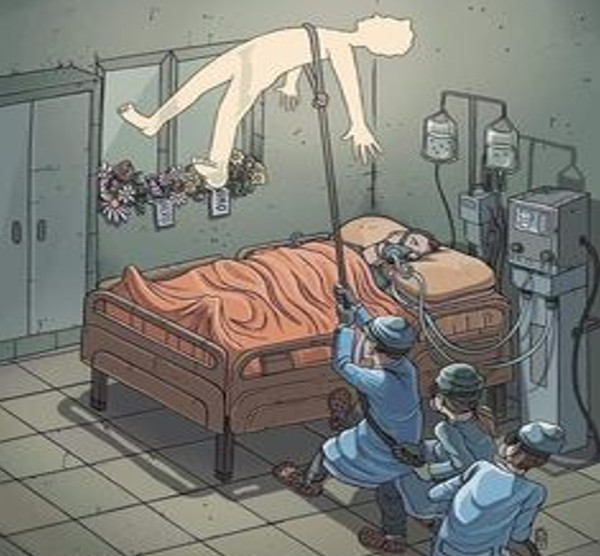

- RECAPITULATION - это вытаскивание из себя (с помощью вдоха и выдоха) всего

прожитого опыта, испытаний, эмоций - плохих и хороших. Может быть

отсуствие электричества наконец, заставит нас делать ПЕРЕСМОТР ВСЕЙ

НАШЕЙ ЖИЗНИ ! Делайте

это весь день, каждый день,

если есть возможность, особенно тем, кто пережил войны и разного рода

катастрофы, или просто инвалид или пожилой человек в инвалидной

коляске. Делайте это в госпиталях и дома, в гостиницах и в транспорте

(как поезда/самолёты/машины, если вы пассажир или застряли на дороге

надолго). Повторяйте каждую деталь пережитого, пока воспоминание этого

навсегда не уйдёт из вашей памяти. Освобождение от всего этого груза

вашей прожитой жизни даёт огромные силы и тепло (когда холодно), но это

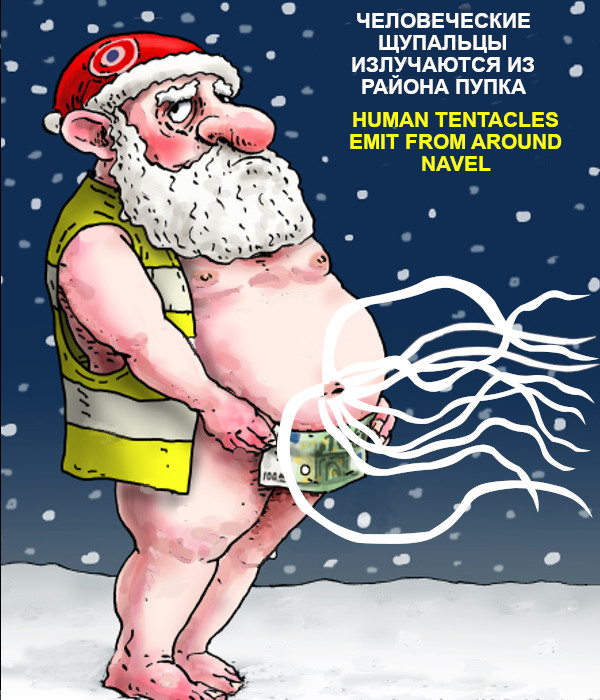

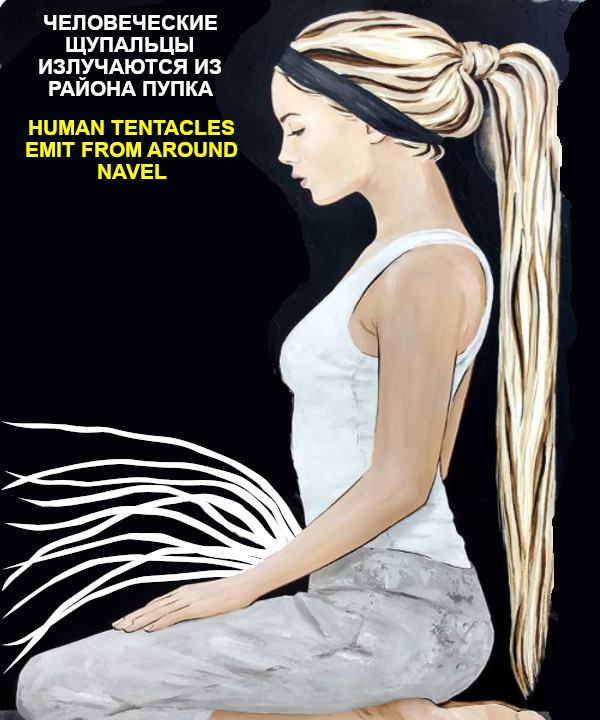

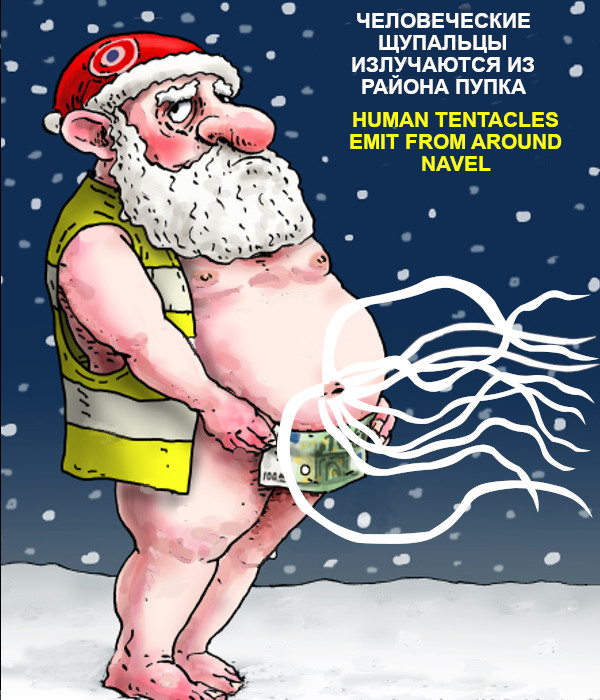

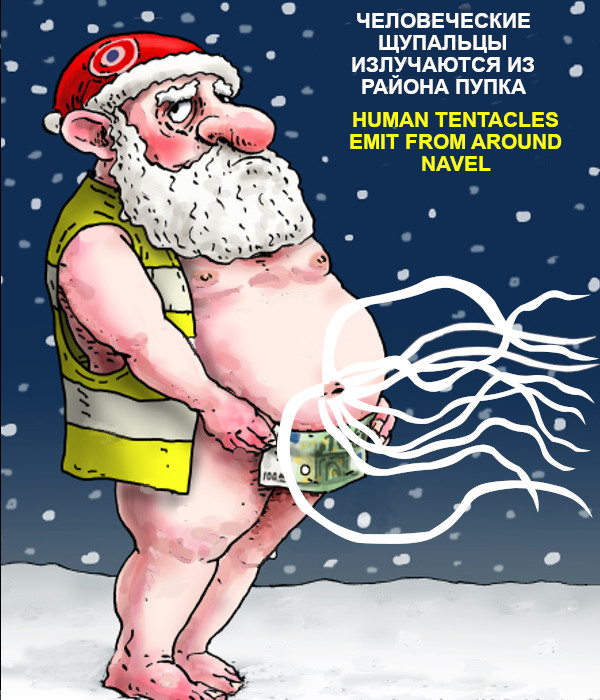

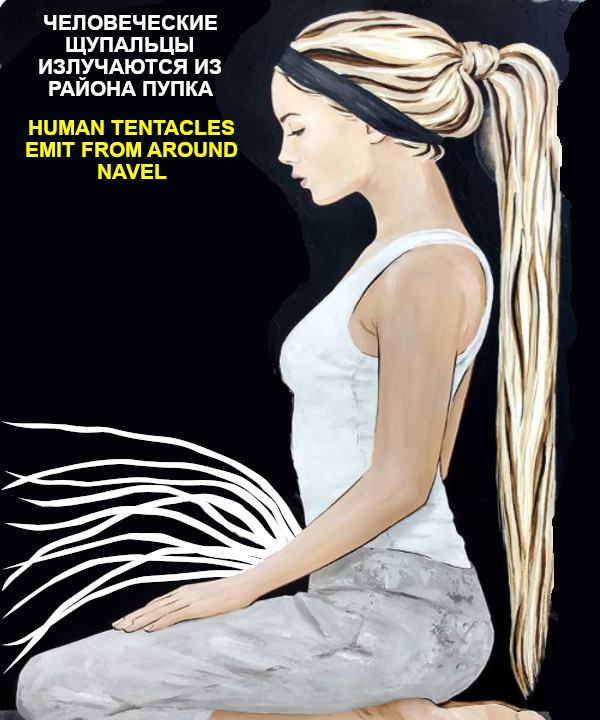

нужно делать правильно, как раз здесь и употребляются ЩУПАЛЬЦЫ,

напоминающие Солнечные Лучи, из нашего Солнечного Сплетения на животе.

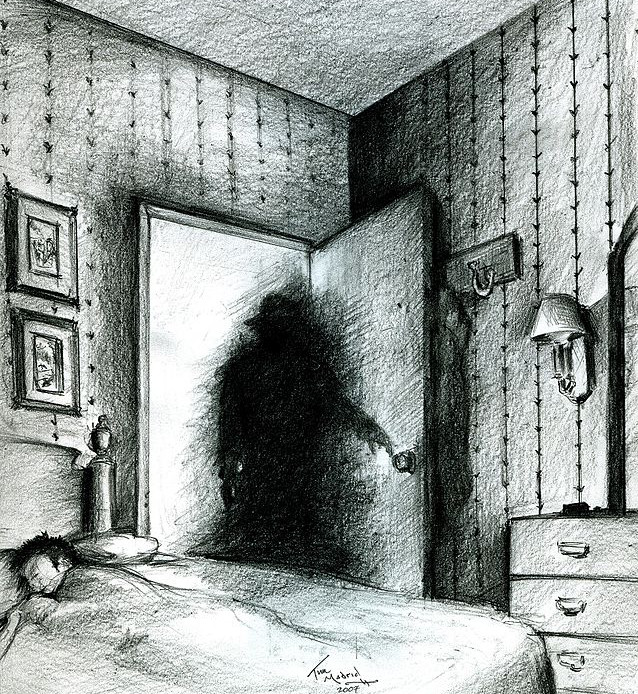

Поверните голову направо (до предела), представьте

сцену/человека/эмоции, которые приходят вам на ум, и которые вы хотите

выдохнуть из себя (первые обычно негативные). Мысленно вытащите свои ЩУПАЛЬЦЫ-Волокна из пупка, сделайте

их как можно длиннее и вцепитесь ими в эту сцену/человека/событие/

эмоции/страх, держите Щупальцы в этой сцене до самого

конца. Затем сделайте глубокий вдох и

медленно-медленно начинайте поворачивать голову влево

(до предела), в то же время вдыхая эту

сцену/человека/эмоции/событие/страх,

не забывая о своих ЩУПАЛЬЦАХ. Остановились, и очень

медленно начинаете

выдыхать воздух и сцену/человека/событие/эмоции/страх из себя,

поворачивая голову вправо (до предела). Останавливаетесь. Затем

быстрые два поворота: влево и вправо (не дышите), и потом голова - останавливается в

центре (дышите), а ЩУПАЛЬЦЫ сами по себе влезут обратно

в район пупка. Побольше практики и станет легче это делать.

Now

we live in difficult times: relentless rains, hails, snow, storms,

tornados, floods and so on. If you are in such situation, surrounded by

water or snow for hours or days, without electricity and Internet, and

don't know what to do next, then do RECAPITULATION. It is removing from

yourself (with the help of breathing) all memories of your life, bad

and good, your experiences and emotions. Do it all day every day, if

you have a lot of free time, especially those people, who survived wars

or all kinds of catastrophies, or just an invalid, or an old person in

a wheelchair. Do it at home or in hospitals, in hotels and transport

(like trains/planes), wherever you find it comfortable. Repeat every

detail of your past memory, till that memory will leave you forever.

Liberation from all that burden of your memories will give (return) you

back a lot of your energy. RECAPITULATION needs to be done the right

way. Here we use

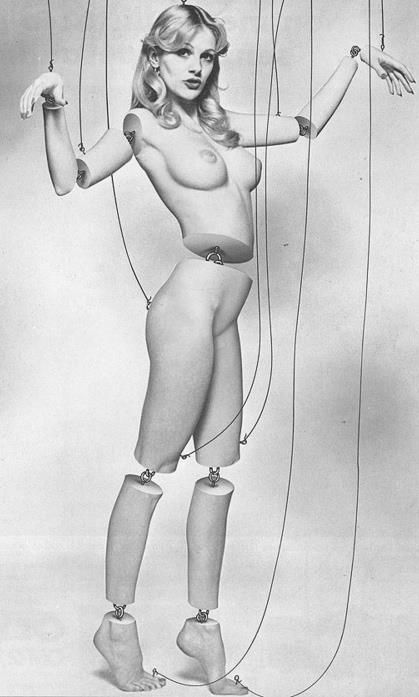

TENTACLES from our Solar Plexus, shining white fibres, resembling Sun

Rays and coming from the area around navel.

Imagine a scene/person/emotion/event/fears from your past, which come

to your mind first, and from which you want to free yourself (usually

negative). Imagine how you stretch your TENTACLES from navel, make them

long, and seize that scene/person/emotion/event/fear with your

TENTACLES, till you finish with that scene. Then turn your head to the

right first and very slowly you start turning your head from right to

left (to maximum) and, at the same time, breath in that scene, every

detail very slowly. Stop.

Then go back: start very slowly moving your head from left to right (to

maximum) and, at the same time, slowly breath that scene out. Stop.

Then two fast turns with your head: to the left and to the right

(without breathing), and stop your head in the centre, you finished.

TENTACLES themselves get back to the navel. With practice it will

become easier.

МОЩНАЯ СИЛА ЧЕЛОВЕЧЕСКИХ

ЩУПАЛЬЦЕВ (отрывки из "ОТДЕЛЬНАЯ РЕАЛЬНОСТЬ")

POWERFUL STRENGTH OF

HUMAN TENTACLES (extracts from "SEPARATE REALITY")

111

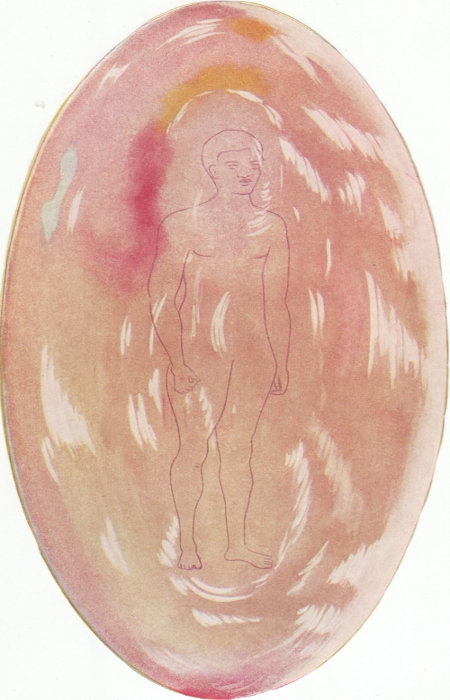

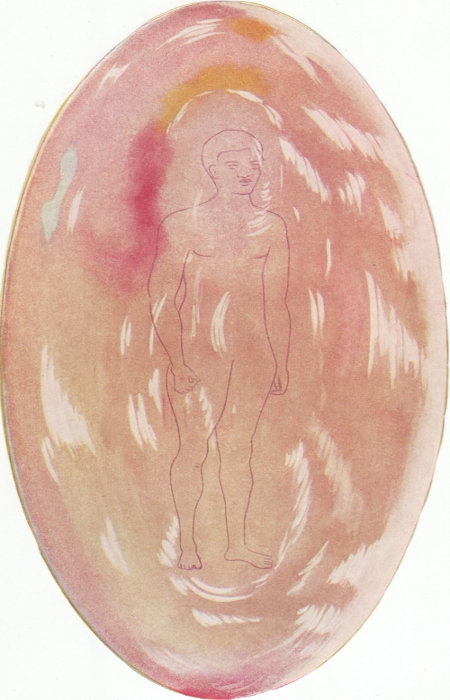

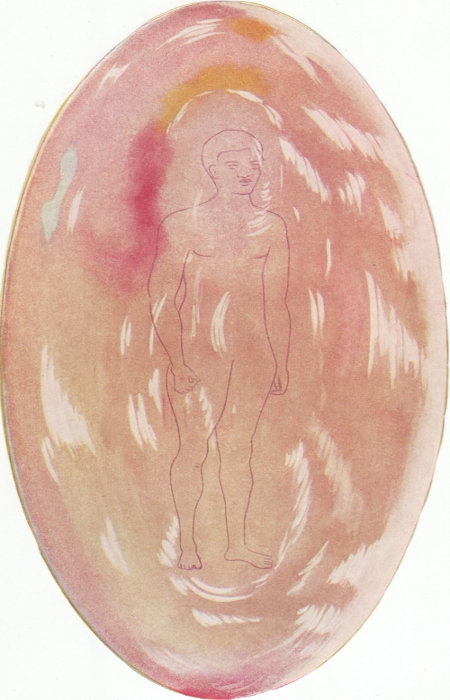

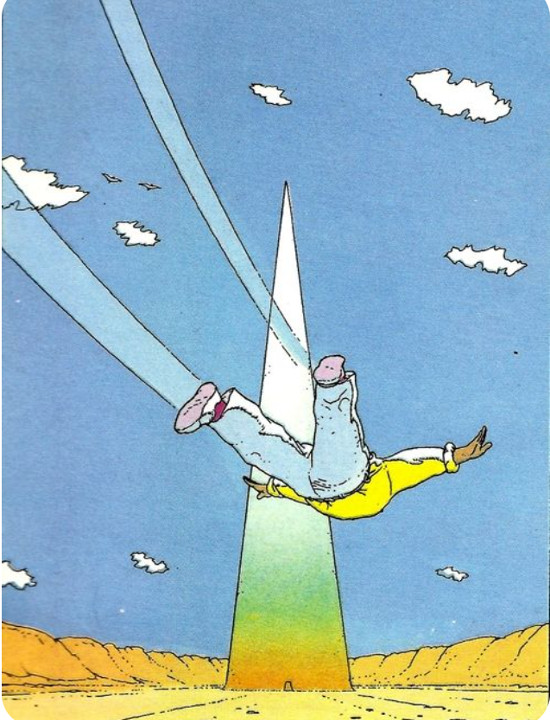

"Don Juan then

explained don Genaro's feat. He said, that he had already told me, that

human beings were, for those, who "Saw," Luminous Beings, composed of

something like fibers of Light, which rotated from the front to the

back, and maintained the appearance of an egg. He said, that he had

also told me, that the most astonishing part of the egg-like creatures,

was a set of long fibers, that came out of the area around the navel;

don Juan said, that those fibers were of the uttermost importance in

the life of a human. Those fibers were the secret of don Genaio's

balance

and his lesson had nothing to do with acrobatic jumps across the

waterfall. His feat of equilibrium was in the way, he used those

"tentacle-like" fibers."

111

"Дон Хуан затем

объяснил поступок Дон Дженаро. Он сказал, что он мне уже говорил, что

люди являются, для тех, кто ВИДИТ, Светящиеся Существа, состоящие из

что-то вроде Волокон Света, которые крутятся с переда - на спину и

сохраняют форму яйца. Он также сказал мне, что самая удивительная часть

Существ, похожих на яйца, был ряд длинных Волокон, которые выходили из

района вокруг пупка; Дон Хуан сказал, что те Волокна были огромной

важности в жизни человека. Те Волокна и были секретом равновесия Дон

Дженаро и его урок не имел ничего общего с акробатическими прыжками

через водопад. Его показ баланса был то, как он использовал те, похожие

на щупальцы, Волокна."

"What are those

tentacle-like fibers, don Juan?"

"They are the

tentacles, that come out of a man's body, which are apparent to any

sorcerer, who Sees. Sorcerers act toward people, in accordance to the

way they See their tentacles. Weak persons have very short, almost

invisible fibers; strong persons have bright, long ones. Genaro's, for

instance, are so bright, that they resemble thickness. You can tell

from the fibers, if a person is healthy, or if he is sick, or if he is

mean, or kind, or treacherous. You can also tell from the fibers, if a

person can See. Here is a baffling problem. When Genaro Saw you, he

knew, just like my friend Vicente did, that you could See; when I See

you, I See, that you can See and yet I know myself, that you can't. How

baffling! Genaro couldn't get over that. I told him, that you were a

strange fool. I think, he wanted to See that for himself and took you

to the waterfall."

"Why do you think, I

give the impression I can See?"

Don Juan did not

answer me. He remained silent for a long time. I did not want to ask

him anything else. Finally he spoke to me and said, that he knew why,

but did not know, how to explain it.

"You think everything

in the world is simple to understand," he said, "because everything you

do is a routine, that is simple to understand. At the waterfall, when

you looked at Genaro moving across the water, you believed, that he was

a master of somersaults, because somersaults was all, you could think

about. And that is all, you will ever believe, he did. Yet Genaro never

jumped across that water. If he had jumped, he would have died. Genaro

balanced himself on his superb, bright fibers. He made them long, long

enough, so that he could, let's say, roll on them across the waterfall.

He demonstrated the proper way to make those tentacles long, and how to

move them with precision. "Pablito Saw nearly all of Genaro's

movements. Nestor, on the other hand, Saw only the most obvious

maneuvers. He missed the delicate details. But you, you Saw nothing at

all."

"Perhaps, if you had

told me beforehand, don Juan, what to look for ..."

He interrupted me and

said, that giving me instructions would only have hindered don Genaro.

Had I known, what was going to take place, my fibers would have been

agitated and would have interfered with don Genaro's. "If you could

See," he said, "it would have been obvious to you, from the first step,

that Genaro took, that he was not slipping, as he went up the side of

the waterfall. He was loosening his tentacles. Twice he made them go

around boulders and held to the sheer rock like a fly. When he got to

the top and was ready to cross the water, he focused them onto a small

rock in the middle of the stream, and when they were secured there, he

let the fibers pull him. Genaro never jumped, therefore he could land

on the slippery surfaces of small boulders at the very edge of the

water. His fibers were at all times neatly wrapped around every rock,

he used. He did not stay on the first boulder very long, because he had

the rest of his fibers, tied onto another one, even smaller, at the

place, where the onrush of water was the greatest.

His tentacles pulled

him again and he landed on it. That was the most outstanding thing, he

did. The surface was too small for a man, to hold onto; and the onrush

of the water would have washed his body over the precipice, had he not

had some of his fibers still focused on the first rock. He stayed in

that second position for a long time, because he had to draw out his

tentacles again and send them across to the other side of the fall.

When he had them secured, he had to release the fibers, focused on the

first rock.

That was very tricky.

Perhaps only Genaro could do that. He nearly lost his grip; or maybe he

was only fooling us, we'll never know that for sure. Personally, I

really think,

he nearly lost his

grip. I know that, because he became rigid and sent out a magnificent

shoot, like a beam of light across the water. I feel, that beam alone

could have pulled him through. When he got to the other side, he stood

up and let his fibers glow like a cluster of lights. That was the one

thing, he did just for you. If you had been able to See,

you would have Seen

that. Genaro stood there looking at you, and then he knew, that you had

not Seen."

112-113

"Для чего нужны эти Волокна, похожие на шупальцы, Дон Хуан?"

"Это - щупальцы, которые выходят из области пупка человека, и которые

видны

любому Колдуну, кто ВИДИТ. Колдуны действуют по отношению к людям,

согласно тому, как они ВИДЯТ их щупальцы. У слабых людей очень

короткие, почти невидимые Волокна-щупальцы; у людей посильнее щупальцы

- длинные и сверкающие. Например, щупальцы Дженаро - настолько яркие,

что они кажутся толстыми.

По этим Волокнам можно определить - здоров ли человек или болен, злой

или добрый или вероломный. По щупальцам также можно определить, может

ли человек ВИДЕТЬ. И вот здесь - проблема, сбивающая с толку. Когда

Дженаро

УВИДЕЛ тебя, он знал, точно также как мой друг Vicente, что ты можешь ВИДЕТЬ; когда я ВИЖУ

тебя, я ВИЖУ, что ты можешь ВИДЕТЬ и всё же сам я знаю, что

ты не можешь. Это ставит в тупик! Дженаро не мог в это поверить. Я

сказал ему, что ты был странным глупцом. Я думаю, что он сам хотел это

ВИДЕТЬ, и поэтому взял тебя на водопад."

"Почему ты думаешь, я создаю впечатление, что могу ВИДЕТЬ?"

Дон Хуан мне не ответил и оставался молчаливым долгое время. Мне не

хотелось спрашивать его о чём-то ещё. Наконец он сказал, что знает

почему, но не знает как это объяснить. "Ты думаешь, что всё в мире

просто, чтобы понять," сказал он, "потому что всё, что ты делаешь, это

- рутина, которая проста для понимания.

На водопаде, когда ты смотрел, как Дженаро двигался по воде, ты думал,

что он - мастер-акробат, потому что сальто было всё, что

приходило тебе на ум.

И это - всё, чему ты будешь верить - он сделал. Однако, Дженаро никогда

не прыгал через тот поток воды. Если бы он прыгнул, он бы погиб.

Дженаро держал себя в равновесии на своих великолепных, сверкающих

Волокнах-щупальцах. Он сделал их достаточно длинными, так чтобы он мог,

скажем так, скатиться по ним через водопад. Он продемонстрировал

настоящий приём - как сделать те щупальцы - длинными, и как с точностью

двигать их. Паблито ВИДЕЛ почти все движения Дженаро. С другой стороны,

Нестор ВИДЕЛ только самые очевидные манёвры. Он пропустил самые

деликатные детали. А ты, ты вообще ничего не ВИДЕЛ."

"Дон Хуан, наверно, если бы ты сказал мне заранее - что искать..."

Он перебил меня, сказав, что дать мне инструкции - только затруднило бы

ситуацию для Дженаро. Если бы я знал то, что произойдёт, мои

Волокна-щупальцы разволновались бы и помешали

бы щупальцам

Дженаро. "Если бы ты мог ВИДЕТЬ," сказал он, "тебе было бы понятно с

первого шага, который Дженаро сделал, что он не соскальзывал, когда шёл

по краю водопада. Он освобождал свои щупальцы. Дважды он заставил их

обернуться вокруг валунов и полагался полностью на валун, как муха.

Когда он добрался до верх и был готов пересечь воду, он сфокусировал

щупальцы на небольшом камне посреди потока, и, когда они были там

закреплены, он позволил Волокнам тянуть его. Дженаро никогда не прыгал,

поэтому он смог приземлиться на скользкой поверхности маленьких камней

на краю воды. Его Волокна всё время были аккуратно привязаны за каждый

камень, который он использовал. Он не оставался очень долго на первом

валуне, потому что свои остальные Волокна он привязал к другому камню,

даже меньше размером, в месте, где скорость потока воды была самой

большой. Его щупальцы снова подтащили его и он на них упал. Это была

наиболее эффектная вещь, которую он сделал. Поверхность была слишком

маленькой для мужчины, чтобы держаться за неё; и поток воды выбросил бы

его тело с обрыва, если бы некоторые его Волокна всё ещё не

фокусировались на первом камне. Он долго оставался в том втором

положении, потому что ему снова пришлось вытащить свои щупальцы и

послать их на другую сторону водопада. Когда он их закрепил, ему

пришлось освободить Волокна, сфокусированные на первом камне. Это было

очень нелегко. Наверно, только Дженаро мог это сделать. Он чуть не

потерял свою хватку; или может быть он только разыгрывал нас, мы точно

никогда не будем знать. Я

лично, реально думаю, он почти потерял свою хватку. Я знаю это, потому

что он потерял гибкость и выдал великолепный луч Света через воду. Я

чувствую, что один только луч мог вывести его. Когда он попал на другую

сторону, он встал и позволил своим Волокнам светиться как скопление

огней. Это была одна вещь, которую он сделал только для тебя. Если бы

ты только был способен ВИДЕТЬ, ты бы увидел это. Дженаро стоял там и

смотрел на тебя, и затем он понял, что ты не ВИДЕЛ."

МОЩНАЯ СИЛА ЧЕЛОВЕЧЕСКИХ

ЩУПАЛЬЦЕВ (отрывки из книги "ВТОРОЙ КРУГ МОГУЩЕСТВА", стр. 252-255)

POWERFUL STRENGTH OF

HUMAN TENTACLES (extracts from the book "SECOND RING OF POWER", p.

252-255)

"Три девушки лежали в середине

огромной, белой, квадратной

комнаты с кирпичным полом...Потолка

у комнаты

не было. Балки, поддерживающие крышу, были затемнены,

и это придавало

эффект

огромной комнаты без крыши...Усевшись

в это положение, похоже, послужило

знаком начала шоу. Лидия встала и начала ходить на цыпочках вдоль краёв

комнаты, близко к стенам. Это не было обычной походкой, а скорее

бесшумное скольжение. По мере ускорения своей скорости, она начала

двигаться, как-будто она скользила, наступая на угол между полом и

стенами. Она перепрыгивала через Розу, Ла Горду, Джозефину

и меня каждый раз, когда она достигала того места, где мы сидели. Я

чувствовал как её длинное платье касается меня, каждый раз когда она

пробегала мимо. Чем быстрее она бежала, тем выше она взбиралась на

стену. Подошёл момент, когда Лидия уже молча бежала по всем четырём

стенам комнаты в 2х метрах над полом. Вид её, бегущей под углом

в 90

градусов к

стенам, был таким неземным, что граничило со сверхестественным. Её

длинное платье придавало всему мистический вид. Земное притяжение,

похоже, не имело никакого эффекта на Лидию, но не на её длинную

юбку:

она падала вниз. Я это чувствовал каждый раз, когда она проскакивала

через мою голову, вытирая моё лицо, словно повисшей занавеской. Она

завладела

моим вниманием на уровне, не поддающемуся воображению. Напряжение

того, что я направил на неё всё своё внимание, было таким сильным, что

у меня в желудке начались конвульсии. Моим

желудком (точнее щупальцами)

я чувствовал её бегущей, и мои глаза теряли фокус. Последней порцией остатка моей

концентрации я видел Лидию,

диагонально шагающей вниз

по восточной

стене, и остановившейся в середине комнаты. Обливаясь потом, пыхтя, она запыхалась, как Ла Горда после её

показа Полёта до этого. Она едва могла держать равновесие. Через

несколько секунд

она прошла на своё место у восточной стены и свалилась на пол как

мокрая тряпка. Я подумал, что она потеряла сознание, но потом заметил,

что она нарочно дышала ртом. После нескольких минут

неподвижности, было достаточно для Лидии, чтобы вернуть свою силу и

сесть

прямо. Встала Роза

и бесшумно побежала к центру комнаты,

повернулась

на пятках и побежала назад туда, где сидела. Её бег дал ей выиграть

необходимый момент, чтобы сделать впечатляющий прыжок. Она подпрыгнула

в воздухе, как баскетбольный игрок, вдоль вертикальной стороны стены, и

её руки направились вверх за пределы высоты стены, что составляло 3.5

метров. Я видел как её тело действительно ударилось о стену, хотя звука

удара не было слышно. Я ожидал, что она упадёт на пол от силы удара, но

она оставалсь висеть наверху, прикреплённая (своими щупальцами! ЛМ) к стене, как маятник.

С того

места, где я сидел, выглядело так, как-будто она держала в левой руке

вроде крюк. Какой-то момент она молча раскачивалась как маятник,

а затем катапультировалась на метр влево, толкая своё тело прочь от

стены правой рукой в тот момент, когда угол её раскачивания был самым

широким. Она повторила раскачивание и катапультирование 30-40

раз. Она

прошла через всю комнату и затем она пошла вверх к балкам крыши, где

она повисла на невидимом крючке (на

своих щупальцах! ЛМ). Когда она была на балках, я понял, что

то, что я считал крюком в её левой руке, реально была такая

способность этой руки (нет, это

помогли её щупальцы! ЛМ), которая сделала возможным ей, сбросить

свой вес

с

неё. Это была та самая рука, которой она атаковала меня две ночи назад.

Её показ закончился тем, что она повисла с балок прямо в центре

комнаты. Внезапно оторвавшись, она упала вниз с высоты 5и метров. Её

длинное платье развевалось вверх и собралось вокруг её головы. Какое-то

мгновенье, до того как беззвучно приземлиться, она стала похожа на

зонтик, перевёрнутый силой ветра. Её тонкое голое тело было похоже на

палку, прикреплённую к тёмной массе её платья.

Моё тело наверно больше почувствовало удар её падения вниз,

чем она

сама. Она приземлилась на корточках и оставалась неподвижной, стараясь

перевести дух...

271-273

"Карлос, ты имеешь ввиду,

что ты не

ВИДЕЛ, как девушки держались (щупальцами) за Волокна Мира?" спросила Ла

Горда.

"Нет, я не ВИДЕЛ."

"Ты не ВИДЕЛ, как они проскользнули через Трещину между Мирами?" Я

пересказал им, что я видел. Они слушали в полном молчании. В конце

моего повествования Ла Горда, казалось, чуть не расплакалась. "Какая

жалость!" воскликнула она, встала, обошла вокруг стола и обняла меня...

довольно интригующая вещь случилась со мной. Самым близким описанием

его будет сказать, что я почувствовал, как мои уши вдруг

разблокировались. Только разблокировку ощущал я, ярче выраженной в

середине моего тела, прямо под пупком (там где Щупальцы), чем в моих

ушах. Сразу после разблокировки

всё стало яснее: звуки, образы, запахи. Тогда я почувствовал

интенсивный гул, который, и что достаточно странно, не мешал мне

слышать

всё вокруг; гул был громкий, но не перекрывал остальные звуки.

Как-будто я слышал гул какой-то другой частью себя, а не ушами. Горячая

волна прошла через моё тело. Затем я вдруг вспомнил то, что я никогда

не видел, как-будто чужая память овладела мной. Я вспомнил, как Лидия

стаскивала себя с двух горизонтальных, красных Волокон, пока шла по

стене. На самом деле она не шла, а собственно скользила по толстой

связке Волокон, которые она держала ногами. Я вспомнил, как ВИДЕЛ, что

она запыхалась и дышала открытым ртом от усилия подтягивания

красных Волокн (нефизических). Причина, почему я не смог держать баланс

в конце

её показа, была в том, что

я ВИДЕЛ её как свет, который облетел комнату

так быстро, что у меня закружилась голова; оно (мои щупальцы) подтянуло

меня из района

моего пупка. Я вспомнил действия Розы, а также Джозефины.

Роза реально разделилась на части: своей левой рукой, держась за

длинные, вертикальные, красные Волокна, которые выглядели как лианы,

свисающие с тёмной крыши. Своей правой рукой она также держала

несколько вертикальных Волокон, которые, похоже, давали ей

стабильность. Она также держалась за те же Волокна своими пальцами ног.

Под конец её показа, она была похожа на фосфорный блеск на крыше. Линии

её тела были стёрты. Джозефина прятала себя

за несколькими Волокнами, которые, казалось,

выходили из пола. Своей поднятой рукой она сдвигала Волокна вместе,

чтобы дать им необходимую ширину и спрятать свою внушительную форму. Её

развевающиеся одежды были надёжной помощью: они каким-то образом,

сжимали её Светимость. Одежды были громоздкими только для глаза,

который смотрел. В конце показа Джозефина, также как

Лидия и Роза, превратилась в пятно света.

В своей голове я мог перейти от

одного воспоминания к другому. Когда я им рассказал о своих настоящих

воспоминаниях, маленькие

Сёстры посмотрели на меня, поражённые. Ла Горда была единнственной, кто

похоже, следовала тому, что со мной случилось. От настоящего

удовольствия она расхохоталась и сказала, что Нагуал был прав, говоря,

что я был слишком ленив, чтобы вспомнить то, что я ВИДЕЛ..."

"The three girls were

lying in the middle of a large, white, square room with a brick floor...The room had

no ceiling. The

supporting beams of the roof had been darkened and that

gave the effect of an enormous room with no top...Rosa, Lidia and Josefina

rolled

counter-clockwise around the room

several times...Lidia

stood up and began to walk on the tips of

her toes along the

edges of the room, close to the walls. It was not a walk proper, but

rather a soundless sliding. As she increased her speed, she began to

move, as if she were gliding, stepping on the angle between the floor

and the walls. She would jump over Rosa, Josefina, la Gorda and myself

every time she got

to where we were sitting. I felt her long dress brushing me, every time

she went by. The faster she ran, the higher she got on the wall. A

moment came when Lidia was actually running silently around the four

walls of the room seven or eight feet above the floor. The sight of

her, running perpendicular to the walls, was so unearthly, that it

bordered on the grotesque. Her long gown made the sight even more

eerie. Gravity did not seem to have any effect on Lidia, but it did on

her long skirt; it dragged downward. I felt it every time she passed

over my head, sweeping my face like a hanging drape. She had captured

my attentiveness at a level, I could not imagine. The

strain, of giving her my undivided attention, was so great, that I

began

to get stomach convulsions; I felt her running with my stomach...

With

the last bit of my remaining

concentration, I saw Lidia walk down on the east wall diagonally and

come to a halt in the middle of the room. She was panting, out of

breath, and drenched in perspiration, like la

Gorda had been after her flying display. She could hardly keep her

balance. After a moment she walked to her place at the east wall and

collapsed on the floor like a wet rag. I thought she had fainted, but

then I noticed, that she was deliberately breathing through her mouth.

After some minutes of stillness, long enough for Lidia to recover her

strength and sit up straight, Rosa stood up and ran without making a

sound to the center of the room, turned on her heels and ran back, to

where she had been sitting. Her running allowed her to gain the

necessary momentum to make an outlandish jump. She leaped up in the

air, like a basketball player, along the vertical span of the wall, and

her hands went beyond the height of the wall, which was perhaps ten

feet. I saw her body actually hitting the wall, although there was no

corresponding crashing sound. I expected her to rebound to the floor

with the force of the impact, but she remained hanging there, attached

to the wall like a pendulum. From where I sat, it looked, as if she

were

holding a hook of some sort in her left hand. She swayed silently in a

pendulum-like motion for a moment and then catapulted herself

three or

four feet over to her left, by pushing her body away from the wall with

her right arm, at the moment, in which her swing was the widest. She

repeated the swaying and catapulting thirty or forty times. She went

around the whole room and then she went up to the beams of the roof,

where she dangled precariously (dangerously lacking in stability),

hanging from an invisible hook. While

she was on the beams, I became aware, that what, I had thought was a

hook in her left hand, was actually some quality of that hand, that

made

it possible for her to suspend her weight from it. It was the same hand

she had attacked me with two nights before. Her display ended with her

dangling from the beams over the very center

of the room. Suddenly she let go. She fell down from a height of

fifteen or sixteen feet. Her long dress flowed upward and gathered

around her head. For an instant, before she landed without a sound, she

looked like an umbrella, turned inside out by the force of the wind;

her

thin, naked body looked like a stick, attached to the dark mass of her

dress...She

landed in a squat position and remained motionless,

trying to catch her breath..."

271-273

"Carlos, you mean you didn't See how girls were holding onto the lines

of the world?" La Gorda asked.

"No, I didn't."

"You didn't See them, slipping through the crack between the worlds?" I

narrated to them, what I had witnessed. They listened in silence. At

the end of my account la Gorda seemed to be on the verge of tears.

"What a pity! " she exclaimed. She stood up and walked around the table

and embraced me...quite an intriguing thing happened to me.

The closest way of describing it, would be to say, that I felt, that my

ears had suddenly popped. Except, that I felt the popping in the middle

of my body, right below my navel (where my tentacles), more acutely, than in my

ears. Right after the popping, everything became clearer; sounds,

sights, odors. Then I felt an intense buzzing, which oddly enough did

not interfere with my hearing capacity; the buzzing was loud, but did

not drown out any other sounds. It was, as if I were hearing the

buzzing with some part of me, other, than my ears. A hot flash went

through my body. And then I suddenly recalled something, I had never

seen. It was, as though an alien memory had taken possession of me. I

remembered Lidia, pulling herself from two horizontal, reddish ropes,

as she walked on the wall. She was not really walking; she was actually

gliding on a thick bundle of lines-fibres, that she held with her feet.

I remembered Seeing her panting with her mouth open, from the exertion

(effort) of pulling the reddish ropes-fibres. The reason, I could not

hold my balance at the end of her display, was because I was Seeing her

as a light, that went around the room so fast, that it made me dizzy;

it pulled me from the area around my navel (my tentacles). I remembered Rosa's

actions and Josefina's as well. Rosa had actually brachiated

(segmented), with her left arm holding onto long, vertical, reddish

fibers, that looked like vines, dropping from the dark roof. With her

right arm she was also holding some vertical fibers, that seemed to

give her stability. She also held onto the same fibers with her toes.

Toward the end of her display, she was like a phosphorescence on the

roof. The lines of her body had been erased. Josefina was hiding

herself behind some lines, that seemed to come out of the floor. What

she was doing with her raised forearm was, moving the lines together,

to give them the necessary width to conceal her bulk. Her puffed-up

clothes were a great prop; they had somehow contracted her luminosity.

The clothes were bulky only for the eye, that looked. At the end of her

display, Josefina, like Lidia and Rosa, was just a patch of light. I

could switch from one recollection to the other in my mind. When I told

them about my concurrent memories, the little Sisters looked at me

bewildered. La Gorda was the only one, who seemed to be following, what

was happening to me. She laughed with true delight and said, that the

Nagual was right, in saying, that I was too lazy to remember, what I

had "Seen"; therefore, I only bothered with, what I had looked at."

Разговор

между Ла Гордой и Карлосом о Человеческой Форме, о Человеческой

Матрице-Штампе, о союзниках (скорее союзницах) и о Полётах - стр.

158-169 :

"Человеческая

Матрица-Штамп, которую ты ВИДЕЛА, был мужчиной или

женщиной?" спросил я.

"Ни

тем, ни другим. Это просто был светящийся человек. Нагуал

сказал, что я могла его попросить что-нибудь для себя, что воин не

может позволить пропустить такой шанс. Но я не могла ничего придумать,

чтобы попросить. Так было лучше. У меня сохранилась прекрасная память

этого. Нагуал

сказал, что

с достаточной энергией воин, может ВИДЕТЬ Матрицу

много, много раз. Каким

великим счастьем это должно быть!"

"Но если

Человеческая Матрица-Штамп то, что скрепляет нас вместе, тогда что

такое Человеческая

Форма?"

"Что-то

липкое, липкая Сила, которая делает нас такими людьми, какие мы есть. Нагуал сказал мне, что Человеческая

Форма не имеет формы. Также, как союзники, которых он носил в своём

сосуде,

это всё, но несмотря на отсуствие формы, Человеческая Форма владеет нами в течение

всей жизни и не оставляет нас до самой смерти. Я никогда не видела Человеческую Форму, но я

чувствовала её в своём теле."

Затем она описала очень сложную серию ощущений, которые у неё были

какое-то количество лет, которые закончились серьёзной болезнью, пиком

которой явилось телесное состояние, которое напоминало мне описание,

как я читал, массивного сердечного приступа. Она сказала, что Человеческая Форма, как

существующая Сила, оставила её тело после серьёзной

внутренней борьбы, которая выражала себя как болезнь..."но

одну вещь я знаю точно. В тот день, когда это случилось, я потеряла

Человеческую Форму. Я стала такой слабой, что днями напролёт я даже не

могла вылезти из своей постели. С того дня у меня не было энергии быть

той старой я. Время от времени я пыталась использовать свои

старые привычки, но у меня не было сил получать от этого удовольствие,

как когда-то. В конце концов я бросила пытаться."

"Какой смысл в

потере своей Формы?"

"Воин должен

потерять свою Человеческую Форму, чтобы измениться, действительно

измениться. Иначе будут только разговоры о переменах, как в твоём

случае. Нагуал

сказал, что

бесполезно только думать или надеяться, что можно поменять

свои привычки. Нельзя ни насколько поменяться, если держаться за Человеческую Форму. Нагуал сказал мне, что

воин знает, что не может поменяться, и всё-таки он подходит по

деловому, стараясь поменяться,

даже когда знает, что не сможет. Это - единственное приемущество воин

имеет над обычным человеком. Воин никогда не расстраивается, если ему

не удаётся поменяться."

"Но ты всё ещё

такая же, Горда, не так ли?"

"Нет, больше

нет. Единственная вещь, которая заставляет тебя думать, что ты тот же

самый, это - Человеческая

Форма. Как

только она уходит,

ты становишься никем."

"Но

ты всё ещё говоришь, думаешь и чувствуешь как всегда, не так ли?"

"Совсем не

так: я - новая." Она засмеялась и обняла меня, как бы

успокаивая ребёнка. "Только

Элиджио и я потеряли

нашу Человеческую Форму,"

продолжала она.

"Это было нашей великой удачей, что мы потеряли её, пока Нагуал был среди

нас..."

"Что ещё ты чувствовала, Горда, когда потеряла свою Форму, кроме потери

своей энергии?"

"Нагуал

сказал мне, что воин без Формы начинает ВИДЕТЬ Глаз. Я

ВИДЕЛА Глаз перед собой, каждый раз когда закрывала свои глаза. Всё

стало настолько тяжело, что я больше не смогла отдыхать; Глаз следовал

за мной, куда бы я не пошла. Я чуть не сошла с ума. В

конце концов, я привыкла к этому."

Сейчас

я даже не замечаю этого, так как это стало частью меня. Бесформенный

воин использует этот Глаз, чтобы начать Полёты. Если у тебя нет

Человеческой Формы, тебе не нужно идти спать, чтобы совершать Полёты.

Глаз впереди тебя тащит тебя каждый раз, когда ты хочешь лететь.

"Где точно этот Глаз, Горда?" Она закрыла свои глаза и двинула своей

рукой из стороны в сторону прямо перед своими глазами, закрывая своё

лицо.

"Иногда Глаз очень маленький, а в другое время он - огромен,"

продолжала она. "Когда он маленький, твой Полёт точен. Но если он

большой, то твой Полёт это как: лететь через горы и почти ничего

не

видеть. Я ещё недостаточно проделала Полётов, но Нагуал сказал мне, что

Глаз - моя выигрышная карта. Однажды, когда я буду по настоящему без

Формы, я Глаз больше не увижу; Глаз станет как я, ничем, и всё-таки он

будет здесь как союзники. Нагуал сказал, что всё

должно быть просеяно через нашу Человеческую Форму. Когда у нас нет Формы,

тогда ничто не имеет форму и всё же всё присуствует. Я не могла понять,

что он имеет ввиду под этим, но сейчас я вижу, что он был совершенно

прав. Союзники - только присуствие и также будет Глаз. Но сейчас этот

Глаз для меня всё. Собственно, имея этот Глаз, мне больше ничего не

нужно, чтобы начать Полёт даже когда я не сплю..."Как ты добилась Полёта, который ты мне показала

вечером?"

"Нагуал научил меня, как

использовать моё тело, чтобы создать огни, потому что мы - Солнечный

Свет в любом случае, поэтому я создаю искры и огни, а они, в свою

очередь, привлекают Светящиеся Волокна Мира. Как только я вижу один,

мне легко к нему прицепиться."

"Как ты прицепляешься?"

"Я

его хватаю." Она сделала жест руками, согнула пальцы до предела и затем

сложила руки вместе, соединила запястья, образовав своего рода чашу с

согнутыми пальцами вверх. "Ты должен хватать волокно как ягуар,"

продолжала она, "и

никогда не отделять запястья. Если ты это сделаешь, то упадёшь вниз и

сломаешь шею." Она остановилась и это заставило меня посмотреть на неё,

ожидая её больших откровений. "Ты

мне не веришь, не так ли?" спросила она и, не давая мне времени

ответить, она села на корточки и снова начала воспроизводить свой показ

искр. Я был спокоен и собран, и мог направить моё полное внимание на её

действия. Когда она щелчком открыла пальцы, каждый фибр её мускулов,

похоже, сразу напрягся. Это напряжение, казалось, сфокусировалось на

самых кончиках её пальцев и спроектировалось наружу в виде Лучей Белого

Света. Влага на её пальцах, собственно, была транспортом, несущим

своего рода энергию, излучаемую её телом.

"Как ты это сделала, Горда?" спросил я, реально восхищаясь ею.

"Я и правда не знаю,"

сказала она. "Я просто делаю это и

делала много, много раз, и всё-таки, я не знаю, как я это делаю. Когда

я хватаю один из тех Лучей,

я чувствую, что меня что-то тащит. Я, правда, ничего больше не делаю,

кроме как дать Волокнам, которые я схватила, тащить меня. Когда я хочу

вернуться назад и чувствую, что Волокно не хочет освободить меня, я

страшно пугаюсь..."

"Как ты научилась дать своему телу держаться за Волокна Мира?"

"Я научилась

этому в

Полёте," сказала она, "но

я правда не знаю как. Всё для женщины-воина начинается в Полёте. Нагуал

сказал мне, также как он сказал тебе, сначала искать мои руки в моих

снах. Я вообще не могла их найти, в моих снах у меня рук не было. Годами

я старалась и старалась найти их...я решила не

есть какое-то время. Lidia

и Josefina

мне помогали. Я ничего не ела 23 дня и потом, одной ночью

я нашла свои

руки во сне. Они были старые, уродливые и зелёные, но они были мои.

Итак, это было начало. Остальное было легко."

"А что было остальное,

Горда?"

"Следующее, что хотел Нагуал, это чтобы я постаралась

найти дома

или здания в моих снах, и смотреть на них, стараясь не развеять

образы. Он сказал, что Искусство Путешественника это - держать образ

его сна, потому что как раз это мы всё равно делаем всю нашу жизнь."

"Что он этим имел

ввиду?"

"Наше Искусство, как обычных людей, в том, что мы знаем, как держать

образ того, на что мы смотрим. Нагуал

сказал, что мы это делаем, но не знаем как. Просто

мы делаем это; то

есть наши тела это делают. Во сне нам придёться делать то же самое,

только во сне нам придёться научится, как это делать. Мы должны

бороться

не смотреть, а просто скользить взглядом и всё-таки держать образ. Нагуал

велел мне найти в моих снах защиту для моего пупка (там наши Щупальцы).

Это взяло долгое

время, потому что я не понимала, что он имел ввиду. Он сказал, что во

сне мы обращаем внимание своим пупком, поэтому он должен быть защищён.

Нам нужно немного тепла

или ощущение, что что-то давит на пупок, чтобы держать образ в наших

снах. Я нашла гальку во сне, которая была размером с мой пупок, и Нагуал заставил меня

искать её день за днём, в водяных дырах и каньонах пока я её не нашла. Для неё сделала пояс и

всё ещё ношу

его день и ночь. Его ношение сделало легче для меня держать образы в

моих снах. Затем Нагуал

дал мне задание идти в определённые места в моих снах. Это у меня

получалось довольно хорошо, но в то время я потеряла мою Форму и начала

ВИДЕТЬ Глаз перед собой. Нагуал

сказал, что Глаз всё поменял, и дал мне команду начать использовать

Глаз, чтобы тащить меня. Он сказал, что у меня нет времени попасть к

моему Двойнику во сне,

но что Глаз - даже лучше. Я чувствовала себя обманутой. Сейчас мне всё

равно, этот

Глаз я использовала,

как только могла. Я

позволила Глазу тащить

себя в

Полётах. Я закрывала глаза и безмятежно засыпала даже днём у себя или

где-то ещё. Глаз

тянул меня и я входила в

другой мир. Большую часть

времени я просто блуждала в нём. Нагуал сказал мне и маленьким Сёстрам, что во

время нашего

менструального периода Полёты становятся Силой. Одна вещь: я становлюсь

немного не в своём уме, становлюсь более отчаяной. И, как Нагуал нам показал, ТРЕЩИНА (между

мирами) открывается

перед нами, женщинами, во время тех дней. Ты - не женщина, и поэтому

для тебя никакой смысл это не имеет, но

за два дня до

менструации, женщина может открыть ту ТРЕЩИНУ и войти через

неё в другой мир. Левой рукой она очертила контур невидимой

Линии, которая, похоже, шла вертикально перед ней на расстоянии

вытянутой руки. "В течении этого периода женщина, если она этого

захочет, может позволить себе отбросить образы мира," сказала Ла

Горда. "Это и

есть Трещина между мирами и, как сказал Нагуал, эта Трещина прямо

перед всеми нами,

женщинами. Причина,

почему

Нагуал

верил, что

женщины-Колдуньи, лучше

чем Колдуны-мужчины,

потому что Трещина

всегда перед

всеми нами, женщинами. Тогда как

мужчинам приходиться её создавать (что нелегко).

Итак, это случилось во время моей менструации, когда я научилась во

время сна летать с помощью Волокон Мира (и наших щупальцев! ЛМ). Я

научилась создавать искры

моим телом, чтобы привлечь Волокна и потом я научилась их хватать. И

всему этому я научилась во сне...Во

время Полётов ты научился звать союзников," сказала она с полной

уверенностью. Я сказал ей, что Дон

Хуан научил меня производить такие звуки. Она, похоже, мне не поверила.

"Тогда

союзники наверно приходут к тебе, так как они ищут Светимость Дон Хуана,"

сказала она, "свою Светимость он оставил с тобой. Он мне сказал, что

у

каждого Колдуна имеется какое-то количество Светимости, чтобы отдать.

Поэтому он передаёт её всем своим детям, в согласии с правилом, который

приходит к нему откуда-то из Бесконечности. В твоём случае, он

даже дал тебе свой собственный позывной." Она щёлкнула языком и

подмигнула мне. "Если ты мне не веришь, тогда почему ты не сделаешь

звук,

которому тебя

научил Дон

Хуан, и посмотри,

придут ли союзники к тебе?"

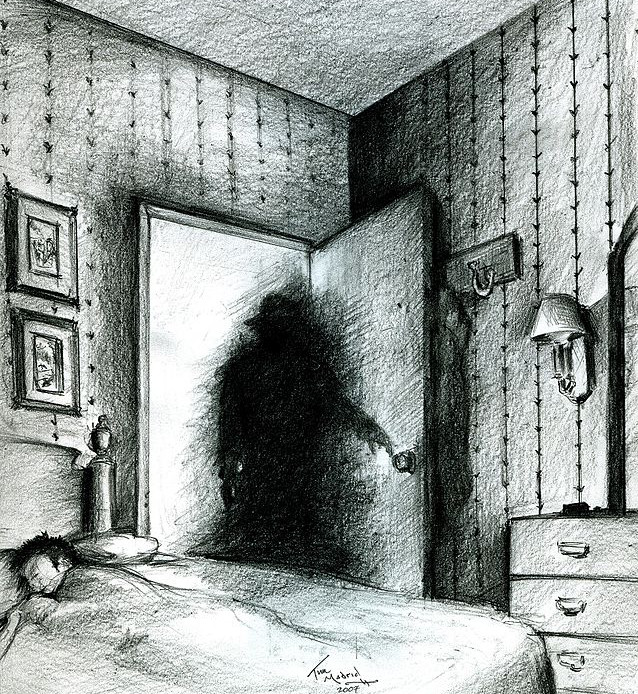

Охоты это делать у

меня не было. Не

потому что я не верил, что мой звук принесёт что-нибудь, а потому что я

не хотел высмеивать её. Какой-то момент она ждала и, когда она была

уверена, что я не собираюсь это делать, она приложила свою руку ко рту

и повторила мой звук дробью в совершенстве. Она играла им 5-6

минут, останавливаясь только чтоб дышать. "Видишь что я имею ввиду?"

спросила она, улыбаясь. "На хрена мой зов Союзникам, даже неважно

насколько он может быть похожим на твой. А сейчас попробуй ты." Я

попробовал и через несколько секунд на мой зов ответили. Ла Горда

подпрыгнула и у меня создалось ясное впечатление, что она больше

удивилась, чем я. Она поспешно заставила меня остановиться, погасила

лампу и собрала мои записи. Она уже было собралась открыть переднюю

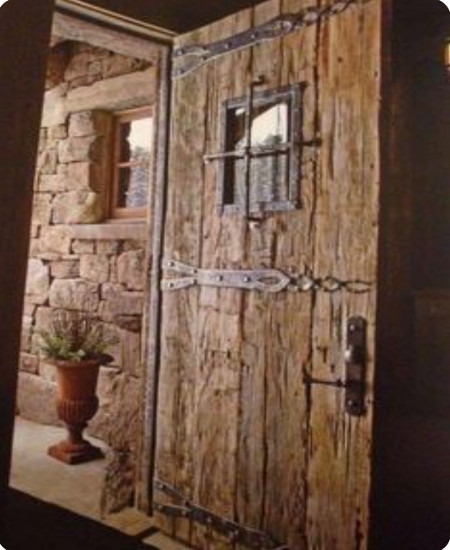

дверь, но тут же остановилась: абсолютно пугающий звук донёсся за

дверью. Мне он казался рычанием и был таким ужасным и негативным, что

заставил нас обоих отскочить назад от двери. Моя физическая тревога

была такой интенсивной, что я бы сбежал, если бы было куда. Что-то

тяжёлое прижималось к двери; из-за этого дверь скрипела. Я посмотрел на

Ла Горду. Она казалась ещё более напуганной и всё ещё стояла с

вытянутой рукой, готовой открыть дверь. Её рот был открыт и она

казалась замороженной в начатом действии. Дверь должна была вот-вот

открыться. Ударов

по двери не было, а просто

жуткое давление и не только на дверь,

но и на дом, и на всё вокруг дома. Ла Горда встала и велела мне быстро

обнять её

сзади, заключив мои руки вокруг её талии над её пупком. Затем она

выполнила странное движение своими руками. Выглядело так, как-будто она

ударяет полотенце, пока держит его на уровне своих глаз. Она проделала

его 4 раза. Потом она сделала ещё одно странное движение, положив

свои руки на середину своей груди ладонями вверх, одну над другой, не

дотрагиваясь друг к дружке. Её локти выдавались прямо из боков. Она

хлопнула

руками, как-будто вдруг схватившись за два невидимых поручня. Медленно повернула свои руки

ладонями

вниз, и потом она сделала очень красивое, сильное движение, которое

казалось, включало все мускулы её тела. Было так, как-будто она

открывала тяжёлую скользящую дверь, которая создавала

огромное сопротивление. Её тело содрогалось от усилий, её руки медленно

двигались, как-будто открывали очень, очень тяжёлую дверь до тех пор,

пока руки не оказались полностью вытянутыми по сторонам. У меня

создалось явное впечатление, что как только она открыла дверь, ворвался

ветер. Этот ветер потащил нас и мы реально прошли через стену. Или

скорее, стены дома прошли через нас, или может быть все трое: Ла Горда,

дом и я прошли через дверь, которую она открыла. Неожиданно я

оказался в открытом поле и мог видеть тёмные формы деревьев и гор

вокруг. Я больше не держался за талию Ла Горды. Шум надо мной заставил

меня взглянуть вверх, и я увидел её, кружащейся наверно 10 футов надо

мной, как чёрная форма огромного воздушного змея. Я почувствовал

невыносимую щекотку в районе моего пупка, и тогда Ла Горда приземлилась

вниз на землю на огромной скорости, но вместо того, чтобы разбиться,

она вошла в мягкую конечную посадку. В тот момент, когда Ла Горда

приземлилась, щекотка в животе превратилась в ужасную,

изнуряющую,

нервную боль. Было ощущение, как-будто её приземление вытаскивало

наружу мои внутренности. Я заорал от боли так громко, насколько

позволял мой голос. Тогда Ла Горда встала рядом со мной, задохнувшись в

отчаянии. Я сидел внизу:

мы снова были в комнате дома Дженаро, где были до этого. Похоже Ла

Горда никак не могла справиться с дыханием, она была вся мокрая от

пота. "Мы должны убраться отсюда," пробормотала она. Поездка к дому маленькие

Сестёр была короткой. Никого из них там не было. Ла Горда зажгла лампу

и повела меня прямо назад, в кухню на открытом воздухе. Там она

разделась и попросила меня искупать её как лошадь, выплёскивая воду на

её тело. Я взял небольшой таз полный воды и начал мягко лить на

неё, но она хотела, чтобы я вымочил её в воде. Она объяснила, что

контакт с союзниками, как тот, который произошёл с нами, создаёт

наиболее ранимое потоотделение, которое должно быть немедленно смыто.

Она заставила меня снять одежду и затем залила меня ледяной водой.

Потом она дала мне чистый кусок материи и мы обсушили себя, пока шли

назад в дом. Она села на большую кровать в передней комнате, после того

как повесила лампу на стену. Её колени были подняты и я мог видеть

каждую часть её тела. Я обнял её голое тело и только тогда я понял, что Дона Солидад имела ввиду, когда

сказала, что Ла

Горда была Женщиной Нагуала. У неё не было Формы, как у Дон

Хуана. Невозможно было думать о ней, как о женщине. Я начал одевать

свою одежду, она отобрала её и сказала, что до того как надеть её,

нужно прогреть её на Солнце. Она дала мне одеяло, чтобы положить на

плечи и достала другое для себя. "Атака союзников была реально

пугающей," сказала она, когда мы сели на кровать. "Нам ещё повезло, что

удалось выскочить из их когтей. Я понятия не имела, почему Нагуал

велел мне идти в дом Дженаро с тобой. Сейчас я знаю: в том доме

союзники всегда сильнее. Они упустили нас на секунду, нам повезло, что

я знала, как выбраться."

"Как

ты это

сделала, Горда?"

"Я понятия не

имею," сказала она. "Я

просто это сделала. Моё тело знало как, я думаю, но когда я хочу

анализировать, как я это сделала, то не понимаю. Это был сложнейший

экзамен для нас обоих. До сегодняшнего вечера я не знала, что я смогла

бы открыть Глаз, но посмотри, чего я сделала: я реально открыла Глаз,

точно как это предсказывал Нагуал.

Я

никогда не была способна это сделать, пока ты не пришёл. Я пыталась, но

это никогда не срабатывало. В

этот раз мой страх тех союзников заставил меня просто схватить Глаз

так, как велел мне Нагуал, тряся его 4 раза в 4х направлениях. Он

сказал, что я должна трясти его, как я трясу постельные простыни, а

потом мне следует открыть его как дверь, держа его посредине. Остальное

было очень легко: как только дверь была открыта, я почувствовала как

сильный ветер тянет меня, вместо того, чтобы отталкивать. Проблема,

сказал Нагуал, это - вернуться. Ты должен быть очень сильным, чтобы

этого добиться. Дженаро,

Нагуал и Элиджио

могли запросто входить и выходить из этого Глаза. Для них Глаз был даже

не Глаз; они говорили: это был оранжевый свет...И такими были Дженаро и Нагуал, когда они летали -

оранжевый свет. Я всё ещё очень мала по масштабу; Нагуал говорил, что

когда я летаю, то выгляжу в небе как коровья лепёшка - у меня не света.

Вот почему возвращение для меня так ужасно. Этой

ночью ты мне помог: дважды потащил меня назад. Причина, почему я этой

ночью показала тебе мой Полёт, потому что Нагуал дал мне приказ

позволить тебе Видеть это, неважно как трудно или неприятно это

выглядит. Моим Полётом, предполагалось, я помогу тебе, точно

также как

ты, предполагалось,

будешь

помогать мне, когда ты показал мне своего Двойника.

Я ВИДЕЛА весь

твой манёвр из

двери. Ты был так занят, чувствуя жалость к Джозефине,

что твоё тело

не заметило моё присуствие. Я

ВИДЕЛА как твой Двойник

вылезал из верхушки твоей головы: он извивался как червяк. Я видела

дрожь, которая началась с ног и прошла через всё твоё тело, а затем

твой Двойник

вылез. Он был как ты, только очень светился. Он был как сам Нагуал, вот

почему Сёстры были парализованы от ужаса. Я знала: они подумали, что это был сам

Нагуал. Но я не могла ВИДЕТЬ всё: я пропустила звук, потому

что

у меня нет к звуку

внимания."

"Прошу

прощенья?"

"Двойник

нуждается в огромном количестве внимания. Нагуал дал такое внимание

тебе, но не мне. Он сказал

мне, что у него

Времени больше не

осталось."

INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT

RECAPITULATION from CARLOS CASTANEDA'S "THE ART OF DREAMING"

148-149

"The Recapitulation of our Lives never ends, no matter how well we've

done it once," don Juan said. "The reason average people lack volition

(willing, choosing, deciding) in their Dreams is, that they have never

Recapitulated, and their lives are filled to capacity with heavily

loaded emotions: like memories, hopes, fears, et cetera, et cetera.

Sorcerers, in contrast, are relatively free from heavy, binding

emotions, because of their Recapitulation. And if something stops them,

as it has stopped you at this moment, the assumption is, that there

still is something in them, that is not quite clear.

"To Recapitulate is too involving, don Juan. Maybe there is something

else I can do instead."

"No. There isn't. Recapitulating and Dreaming go hand in hand. As we

regurgitate (vomit up) our lives, we get more and more airborne."

Don Juan had given me very detailed and explicit (specific, clearly

defined) instructions about the Recapitulation. It consisted of

Reliving the Totality of one's life experiences by Remembering every

possible minute detail of them. He saw the Recapitulation as the

essential factor in a Dreamer's Redefinition and Redeployment of Energy.

"The Recapitulation sets Free Energy imprisoned within us, and without

this liberated Energy Dreaming is not possible." That was his

statement. Years before, don Juan had coached me to make a list of all

the people I had met in my life, starting at the present. He helped me

to arrange my list in an orderly fashion, breaking it down into areas

of activity, such as jobs I had had, schools I had attended. Then he

guided me to go, without deviation, from the first person on my list to

the last one, Reliving every one of my interactions with them. He

explained, that Recapitulating an event starts with one's Mind,

arranging everything pertinent (relevant) to what is being

Recapitulated. Arranging means Reconstructing the Event, piece by

piece, starting by Recollecting the Physical Details of the

surroundings, then going to the person, with whom one shared the

interaction, and then going to oneself, to the examination of one's

feelings. Don Juan taught me, that the Recapitulation is coupled with a

Natural, Rhythmical Breathing. Long Exhalations (breathing out) are

performed, as the head moves gently and slowly from right to left; and

long Inhalations are taken as the head moves back from left to right.

He called this act of moving the head from side to side "fanning the

event." The Mind examines the event from beginning to end, while the

body fans, on and on, everything the Mind focuses on. Don Juan said,

that the Sorcerers of Antiquity, the Inventors of the Recapitulation,

viewed Breathing as a Magical, Life-Giving Act and used it,

accordingly, as a Magical Vehicle; the Exhalation, to eject (expel,

throw out) the Foreign Energy, left in them during the Interaction

being Recapitulated and the Inhalation to Pull back the Energy, that

they, themselves, left behind during the Interaction. Because of my

academic training, I took the Recapitulation to be the process of

analyzing one's Life. But don Juan insisted, that it was more involved,

than an intellectual psychoanalysis. He postulated (demanded, made

claim for) the Recapitulation, as a Sorcerer's Ploy (tactic) to induce

a minute, but Steady Displacement of the Assemblage Point. He said,

that the Assemblage Point, under the Impact of reviewing Past Actions

and Feelings, goes back and forth between its present site and the site

it occupied, when the event, being Recapitulated, took place."

ИНТЕРЕСНЫЕ ФАКТЫ О ПЕРЕСМОТРЕ СВОЕЙ ЖИЗНИ -

Искусство Полёта" - Карлос Кастанэда

148-149

"Обзор наших жизней никогда не заканчивается, неважно как хорошо мы это

сделали однажды," сказал Дон Хуан. "Причина, почему у обычных людей

отсуствует желание в своих снах, в том, что они никогда не делали

обзора, и их жизни до краёв наполнены тяжёлыми эмоциями, как:

воспоминания, надежды, страхи и т.д."

"Колдуны, в противоположность этому, относительно свободны от тяжёлых,

связающих нас, эмоций, по причине обзора своих жизней. И если их

останавливает

что-то, как это остановило тебя в этот момент, есть предположение, что

там всё ещё осталось то, что не совсем ясно."

"Обзор занимает слишком много времени, Дон Хуан. Может есть что-то ещё,

что я мог бы сделать вместо этого."

"Нет. Ничего нет. Обзор и Полёты идут рука об руку. Когда мы

освобождаем наши жизни, мы делаемся более лёгкими, воздушными."

Дон Хуан дал мне очень детальные и ясные инструкции об Обзоре. Это

выражается в том, чтобы полностью пережить свою жизнь путём

воспоминаний каждой возможной детали. Дон Хуан видел Обзор, как

необходимый фактор в переопределении Путешественника и в

перераспределении его энергии.

"Обзор освобождает Свободную Энергию, заключённую в нас, и без этой

Свободной Энергии, Полёты - невозможны." Это было его заявление. Годы

до этого,

Дон Хуан тренировал меня сделать список всех людей, которых я встретил

в своей жизни, начиная с настоящего (или последнего). Он помог мне

составить список в нужном порядке, разбив его по районам активности,

как например, работы я имел, школы я посещал. Затем он подсказал мне

идти по списку, ен отклоняясь, с первого человека, в моём списке, до

самого последнего, пережить каждую встречу с ними. Он объяснил: обзор

события начинается с того, что мой ум избирает всё относящееся к тому,

что будет вспоминаться. Распределение означает вновь восстановить

событие, кусок за куском, начиная с воспоминаний физических деталей

окружающего мира, затем переходить к человеку, с которым были

отношения, а потом переходя к самому себе, к просмотру своих чувств.

Дон Хуан учил меня, что Пересмотр соединён с естественным, ритмическим

Дыханием. Выполняются Длинные Выдохи пока голова мягко и медленно

двигается справа-налево; и длинные Вдохи берутся, когда голова

двигается слева-направо. Он называл это действие - движения головы из

стороны - в сторону - "вентилирование события".

Разум осматривает событие с начала до конца, пока тело (голова) делает

веерное движение снова и снова на всём, на чём фокусируется Разум. Дон

Хуан сказал, что Древние Колдуны, изобретатели Пересмотра,

рассматривали Дыхание - МАГИЧЕСКИМ, жизненно-утверждающим актом, и

использовали его, соответственно, как МАГИЧЕСКИЙ ТРАНСПОРТ; Выдыхание,

чтобы выбросить чужую энергию, оставленную в этих Колдунах во время

общения, была пересмотрена, и Вдыхание это - втянуть назад в себя

Энергию, которую сами Колдуны оставили там во время общения. Из-за

моего академического образования, я принял Пересмотр, как процесс

анализа своей жизни. Но Дон Хуан настаивал, что это намного больше, чем

умственный психоанализ. Он доказывал, что Пересмотр, это - тактика

Колдуна, чтобы начать маленький, но постоянный Сдвиг своей Точки

Восприятия. Он сказал, что Точка Восприятия, под влиянием осмотра

прошлых действий и чувств, двигается взад-вперёд между настоящим её

положением и тем положением, которое Точка Восприятия занимала в момент

того прошлого события, которое пересматривается."

ИНТЕРЕСНЫЕ ФАКТЫ ИЗ КНИГИ "ОТДЕЛЬНАЯ РЕАЛЬНОСТЬ"

- INTERESTING FACTS FROM

THE BOOK "SEPARATE

REALITY"